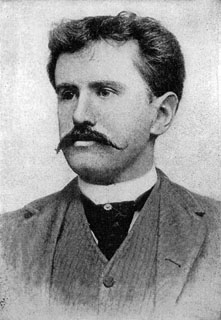

1886 Self-portrait

1886 Self-portrait  1860 - photo Carjat

1860 - photo CarjatIn honor to my favorite artist of all time.

In 1900, Monet has become famous. On the occasion of an exhibition in Paris a journalist, Thiébault-Sisson, made him tell his life. On November 26, 1900 the newspaper "Le Temps" published this autobiography in which Monet builds himself his legend. The text is spicy but doesn't always reflect reality faithfully ...

My History

I am a Parisian of Paris. I was born there in 1840, under the reign of the good king Louis-Philippe which was an epoch centred on business interests and in which the Arts were regarded with real derision. As it was, my childhood was spent at the Havre where my father had settled in 1845 in order to better pursue his own business interests and as it happened, this childhood of mine, was essentially one of freedom. I was born undisciplineable. No one was ever able to make me stick to the rules, not even in my youngest days. It was at home that I learned most of what I do know. I equated my college life with that of a prison and I could never resolve to spend my time there, even for four hours a day when the sun was shinning bright, the sea was so beautiful and it was so good to run along the cliff-tops in the fresh air or frolic in the sea.

Up until the age of fourteen or fifteen, much to my father's great disappointment, I continued this very irregular but healthy way of life. Somehow, in between, I did acquire the rudiments of a basic education including some proficiency at spelling. My studies went no further and did not cause me too much trouble, as I was able to interweave them with a number of distractions. I ornamented the margins of my text books, I decorated the blue paper of my exercise books with ultra fantastic designs and represented in the most irreverant manner possible, the features of my masters - either drawingtheir faces in front view or in profile.

I became very quickly adept at this game. At fifteen, I was known by the whole of Le Havre as a caricaturist. My reputation was so well established that I was commissioned by everyone for these types of portraits. It was in effect, in consideration of the sheer number of commissions that I received as well as the insufficiency of the allowance that I received from my mother, that prompted the audacious decision that I made to charge a fee for my portraits. This of course, scandalised my family. I would charge ten to twenty francs depending on whether I liked the look of my clients or not and this method worked extremely well. In a month, the number of clients had doubled and I was able to charge a fixed rate of twenty francs without reducing in any way the demand. Had I continued this way, I would today be a millionaire!

Thus, by this means, I became someone of importance in the town. There, along the shop front of the only framers in business at Le Havre, were my caricatures, insolently sprawled-out in groups of five or six, to be seen in full in little gold frames, under glass like real works of art. Moreover, when I saw strollers gathering to gap at them with admiration and cry "It is so and so!", I was bursting with pride.

I should say, however, that there was a flaw to this otherwise perfect situation. There was often, in this same shop window, hanging just above my own works, a number of maritime scenes that I found, along with most of the inhabitants of the Havre, revolting. I was so vexed at having to endure this enforced contact, that I did not tary to slander this idiot who, thinking himself an artist had dared to sign his works "Boudin". For me, who had been used to Gudin's seascapes - with their arbitrary colourations, false touches and invented perspectives so much in use by fashionable artists at the time - Boudin's sincere little compositions with his correctly deliniated little figures, his pleasant boats, his ever so perfect skies and water, drawn and painted only from nature, held no artistic value for me. His fidelity seemed suspect. Hence, his paintings inspired me with a terrible aversion and without even having met the man, I disliked him intensely. Often, the framer would say: "You should meet Mister Boudin. Despite what is said about him, he is a professional who knows his work. He studied in Paris at the Academy Beaux-Arts. He could give you some useful advice."

But I resisted, dug my heals in . What could I possibly learn from such a ridiculous fellow?

Despite myself, however, the day did arrive when fate thrust me into Boudin's presence. He was at the back of the shop and I had not noticed him as I entered. The framer immediately took the opportunity to introduce me saying: "See here, Mister Boudin, this is the young man with so much talent for caricature!" Boudin immediately coming towards me, complimented me with his gentle voice and said: "I always look at your sketches with pleasure; they are amusing, animated, they seem to have been done with ease. You have talent, one can see that straight away. But you are not, I hope, going to keep doing the same thing. It is very good for starting off, but you will get bored with just doing caricatures. Study, learn to look, paint and draw. Do some landscapes. It is so beautiful the sea and sky, animals, people and trees just as nature made them, with their characters, their true essence of being, in the light, within the atmosphere, just as things are."

But Boudin's exhortations left no impression on me even if, after all, the man himself was agreable to me. He was convinced, sincere. I could feel it, but I could not appreciate his paintings and when he offered to take me with him to paint outdoors in the open countryside, I always found a pretext and refused politely. But when summer came, I was more or less free to dispose of my time as I wished and I had no feasible excuse left to give him and gave in. Thus it was, that Boudin - with his inexhaustable kindness - took it upon himself to educate me. With time, my eyes began to open and I really started to understand nature. I also leaned to love it. I would analyse its forms with my pencil. I would study its colourations. Six months later - not withstandings my mother's objections who was seriously becoming worried about my frequentations of a man like Boudin, I squarely announced to my father, that I intended to become a painter and was moving to Paris to learn.

"You will not get a penny!"

"I shall do without."

In effect, I was able to do without. I had already, long ago, managed to 'line my purse'. The sales from my caricatures had taken care of that. I had often been able to execute in one day , seven or eight commissioned portraits. At a "Louis" for each, my income had flourished and I had taken the habit from the start, to deposit the revenue with one one of my aunts, keeping for my pocket money only insignificant amounts. At sixteen, with two thousand francs, one believes onself to be rich! Armed with references acquired through admirers of Boudin who had connections with Monginot, Troyon and Amand Gautier, I promptly left for Paris without a care in the world.

To begin with, it took a while for me to find my feet. I went to visit the artists to whom I had been introduced. I received some excellent advice but also some appalling suggestions. Was it not the case that Troyon had tried to make me attend Couture's workshop? Needless to say, how vehemently I had refused that idea. It even had the effect of cooling my estimation of Troyon, at least for a short while. I stopped seeing him and associated instead only with artists who were looking for something. At that time, I met Pissarro who had not yet thought of being a rebel and was simply working in Corot's style. I felt this to be a good model to emulate and I followed suit. Having said this, for the whole duration of my four years in Paris - which was interdispersed with frequent visits to Le Havre anyhow - it was mainly Boudin's advice that I adhered to, even given my inclination to enlarge upon nature.

I reached my twentieth year and the time when I should be conscripted into the army was drawing near. This did not provoke fear in me nor did it worry my family. My escape had not been forgiven and if they had let me live my life as I wished for those four years, it was only because they hoped to bring me back to the fold once faced with military service. They assumed, that having had the opportunity to try and make my own way in the world, I would soon tire of it and return home, sensibly, getting-down to my family's business interests. If I refused, they would cut-off my allowance or should I turn-out badly, they would simply let me go.

They were wrong. The seven years which to many others seemed so difficult, appeared to me to be full of charm. A friend - who was a "chass d'Af" and who loved military life, had communicated to me his enthusiasm and suffused me with his sense of adventure. Nothing seemed more attractive than the endless trekking under the sun, the raids, the crackle of the gun-powder, the sabre-rattling, the nights spent under canvass in the desert and I imperiously waved aside all my father's objections. I was 'bad news' and I obtained, on demand, that I should be sent to a regiment in Africa and left.

I spent two really charming years in Algeria. There was always something new to see and in my spare time, I tried to capture what I saw. You cannot imagine the extent of what I learned and how much my ability to see improved. I was not immediately aware of this. The impressions of light and colour that I gained there were, to some extent, put aside later, but the kernal of my future researches came from them.

At the end of the two years, I became seriously ill. I was sent back home. My six months of convalescence were spent drawing and painting with renewed fervour. Seeing me thus, so determined despite the fact that I was very weak with fever, my father became convinced that nothing would sway me from my resolve and that no obstacle could stand in the way of my chosen vocation, so that as a result of both lassitude as well as fear of losing me should I go back to Africa (as the doctor had warned), he relented and decided towards the end of my leave, to buy me out.

"But, it must be well understood that you are to work seriously this time. I want to see you in a workshop, under the discipline of a well-known master. If you return to your previous independence, I will cut off your allowance without any concessions. Is that understood?" His plan only half satisfied me, but I was well aware that since my father was for once, prepared to consider things from my point of view, it was necessary not to refuse.

I accepted and it was settled that I should, in Paris, be under the artistic tutelage of the painter Toulmouche, who had just married one of my cousins. He would guide me and would provide regular reports on my work.

One sunny morning, I arrived at Toulmouche's with a pile of my sketches which he greatly appreciated. "You have promise but you will have to channel your impetus. You will be sent to Mister Gleyre. He is the kind of sedate and wise master you need." So I set up my easel, grumbling, in the studio that this famous artist ran for students. The first week, I worked there conscientiously and produced with as much application as dash, a life-drawing that Mister Gleyre corrected on the Monday.

The following week, when he passed in front of me, he sat down and squarely positioned on my chair, looked at my piece. I could then see him turn around, inclining his serious face with a satisfied air and I heard him say to me while smiling: "Not bad, not at all bad this, but it is too much like the real model. You have a stocky man and you depict him as stocky. He has enormous feet and you reproduce them. It is very ugly. Remember, young man, that when one executes a face, one should always think back to the Classical. Nature, my friend, serves well as a means to study but offers no real interest. Style is the only thing that matters."

I was flabbergasted. The truth, life, nature - all that provoked emotions in me - all that constituted for me the real essence and the unique "raison d'être" of art, did not exist for this man! I would not stay with him. I did not believe myself to have been born to follow his pursuit of lost illusions and other nonsenses. What was the use of persisting?

I did however, wait a few weeks so as not to exasperate my family. I did continue to attend but just stayed long enough to execute a rough sketch copied from the model and to be there for the correction. I then cleared out. I had in any case, found some companions that I liked at the studio. They had nothing superficial about their natures. These were Renoir and Sisley whom I would not from then on, loose sight of. There was also Bazille, who immediately became an intimate friend and would have made a name for himself, had he lived. Neither of them manifested any more than I did, any enthusiasm for an education, which both contravened their sense of logic as well as their temperaments.

I immediately preached revolt to them. Our exodus resolved upon, we left and took a studio which we shared, Bazille and I.

I forgot to tell you that I had recently made the aquaintance of Jongkind. It was during my convalescence-leave, one beautiful afternoon when I was working near Le Havre at a farm. A cow was grazing in a field and the idea came to me to draw the animal. But this animal was capricious and kept moving with every second that went by. With my easel held in one hand and my stool in the other, I would follow her in order to regain as best as was possible, my point of view. My antics must have been very funny to be sure, as I heard behind me, a great roar of laughter. I turned around and saw a giant bursting out with laughter. But this giant was a good sort. "Wait for me to help you", he said. The giant then, with enormous strides came up to the cow and got hold of its horns in order to contraint it to 'pose'. The cow, naturally, not being used to this sort of thing, resisted. This time, it was my turn to explode with meriment and the giant, crestfallen, let go of the beast and came over to me for a little chat.

He was an English man, just passing through, greatly in love with painting and very informed about what was going on in our country.

"So, you paint landscapes", he said.

"Well, yes."

"Do you know Jongkind?"

"No, but I have seen some of his paintings"

"What do you think about it?"

"It is very good"

"Too right, do you know that he is here?"

"Are you sure?"

"He lives at Honfleur. Would you like to meet him?"

"Certainly, I would. Are you one of his friends ?"

"I have never seen him, but as soon as I learned he was here, I sent him my calling card. It is a good opportunity and I am going to invite him and yourself, for lunch."

To my great surprise, the English man kept to his word and the following Sunday, the three of us had lunch together. Never was a meal so gay. It took place outdoors in a little country garden under some trees and the food was wholesome country fare. But, with a full glass of wine in his hand, sitting between two obviously sincere admirers, Jongkind did not quite feel at ease. The unexpected aspect of this meeting amused him but he was not accustomed to this sort of thing. His painting was too new and far too artistic to be appreciated in 1862 at his prices. Moreover, no one was as bad at making himself valued, as he was.

He was a straight-forward and simple kind of man, who could hardly speak bad French and was very shy. But he was very outgoing that day. He asked to see my sketches, invited me to come and work with him, explained the whys and wherefores underlining his work and thereby, completed the training that I had already received from Boudin. He became from this moment, my true master and it to him, that I owe the definitive training of my eyes.

I saw him again often in Paris. No need to say how much my painting improved. The progress that I made was rapid and three years later, I was exhibiting. The two seascapes that I had sent were received and given pride of place, hung high-up in good view. It was a great success. The same unanimous praise was given in 1866 for a large portrait that you saw at Durand-Ruel and which was there for a long time "The Woman in Green". The newspapers carried my name right to Le Havre and my family, at last, granted me some estimation. With this estimation came a renewed allowance. I was swimming in opulence, at least, for a while as we were to fall out again later. I was ready to recklessly hurl myself into the open.

It was a rather dangerous novelty. No one had attempted it, not even Manet, who innovated only later, after me. His painting was still very conventional and I still remember the contemptuous way in which he spoke of my beginnings. It was in 1867, my style had began to stand out, but for all that, it was far from revolutionary. I was still a long way off from my adoption of the principle of the division of colours - which turned so many people against me, but I was partially trying it out and would practice different effects of light and colour which contravened received ideas. The selection committee, which was all in my favour in the beginning, turned against me and when I presented my new painting to the 'Salon', I was shamefully rejected.

I did however, find a means of exhibiting, but elswhere. Touched by my entreaties, a dealer who had his shop at the 'rue Auber', did consent to show a seascape of mine which had been refused by the 'Palais de L'Industrie'. There were cries of indignation. One evening as I stopped in the road, joining a group of strollers to hear what was being said of me, I saw Manet arriving with two or three of his friends. The party stopped, looked and Manet shrugging his shoulders, cried-out contempteously: "Look at this young man who wants to paint from nature; as though the ancients had never thought about it!"

Manet held an old grudge against me. At the 'Salon' of 1866, the day of the opening, he had been met from the start, with acclamations. "Excellent, my friend, your picture!" Hand-shakes, 'bravos' and felicitations ensued. Manet - as you can imagine - was exultant. You can also imagine his surprise when he discovered that the canvas which was getting so much praise, was one of mine. It was "The Woman in Green". As fate would have it, just as he was trying to slip away, he stumbled on a group of people made up of Bazille and myself. "Ah, my friend, it is disgusting, I am furious! One is only complimenting me on a painting that is not even by me. One would think it is a hoax."

When, the next day, Astruc informed him that he had voiced his disatisfaction in front of the author of the painting and proposed to introduce him to me, Manet with a shrug, flatly refused. He retained the grudge for the bad turn I had played on him, entirely unwittingly. For once he had been praised for a masterly touch and this touch was not his. This was a bitter blow for someone which such sensitivity.

It was not until 1869 that I met him again, but this time, we became friends immediately. From the first meeting, he invited me to join him every evening in a café of the 'Batignolles' where he and his friends would gather to talk at the end of a day spent at their studios. I would meet there, Fantin-Latour and Cézanne, Degas - who arrived shortly afterwards from Italy, the art critic Duranty, Emile Zola who was just starting-off in the literary world and a number of others. I would take Sisley, Bazille and Renoir. There was nothing more interesting than these discussions with their perpetual differences of opinion. Our mind and souls were stimulated. We would encourage each other to make unbiased and sincere researches. We would nourish each other with enthusiasm which had the power to sustain us for weeks on end, until we were able to give definite form to the idea. One would always leave, all the better immersed, the will stronger, our thinking more defined and clear.

The war came. I had just got married. I went to England and found, in London, Bonvin and Pissarro. I also experienced poverty there. England did not want our paintings and things were hard. But as fate would have it, I met Daubigny who, in the past had shown some interest in me. At the time, he was doing views of the Thames which were very well liked by the English. My situation stirred his compassion. "I can see what you need. I will find a dealer for you", he said. The next day, I made the acquaintance of Durand-Ruel.

Durand-Ruel, became for us, our saviour. For more than fifteen years, my painting as well as that of Renoir, Sisley and Pissarro had no other market than through him. One day came when he was forced to restrain himself and buy from us less regularly. We thought ruin was facing us but it was success that was just about to come. Offered to Petit and the Boussod, our works found through them some buyers. They were judged not to be quite as bad as previously thought. At Durand-Ruel, they were not wanted, but once placed with others, confidence increased and people bought. The 'pendulum was in motion'. Today, everyone wants to know us.

Claude Monet

Presented by Thiébault-SissonPublished on November 26th 1900 in "Le Temps" newspaperTranslation by Louise McGlone

Photographer foureyes .

Photographer foureyes .

Photographer charles jones

Photographer charles jones Photographer Yuliya Shevchenko

Photographer Yuliya Shevchenko

Photographer Marc Adamus

Photographer Marc Adamus Photographer Bengt Ekelberg

Photographer Bengt Ekelberg and my favorite short story of all time.

and my favorite short story of all time.